The sometimes dusty, sometimes muddy road from the Princes Highway leads to one of East Gippsland’s most remote and undisturbed coastal locations. Quiet and peaceful, Wingan Inlet in Croajingolong National Park is a welcome destination in our hectic world.

At the end of the West Wingan Road, on the western shore of the inlet, modest camping and day visitor facilities are found in a setting of large, old Red Bloodwoods (Corymbia gummifera). Wingan Inlet is the most southern natural occurrence of the species.

This is a remarkable place to camp. Wrens, robins, honeyeaters and tree creepers are common. A male Satin Bowerbird sometimes raids camps for small blue items to decorate his bower to attract females. The Kookaburras can be overly dependent on campers’ food and need a watchful eye. Lace Monitors cautiously move through the campground flicking their long tongues at anything that may be edible and are ready to scurry up the nearest tree when disturbed. Occasionally a Red-bellied Black Snake will seek out sunny patches under the Bloodwood canopy.

As celebrated by Slim Dusty’s, “When the Currawongs Come Down”, Pied Currawongs spend the winter among the Bloodwoods, feed on Blue Olive Berry (Elaeocarpus reticulatus) and return to the mountains in the summer.

Plant species flourish in the deep sandy soils through the campground, such as the Giant Trigger Plant (Stylidium laricifolium), and the delicate climber, Bearded Tylophora (Tylophora barbata).

After dark Yellow-bellied Gliders screech as they glide from one Bloodwood and scramble up the next. They feed on the Bloodwoods, creating a v-shaped groove in the bark with their incisors to encourage a flow of the bright red sap. Weighing no more than about 40 grams, the Eastern Pygmy Possum feeds on Banksia nectar and pollen and is much harder to see.

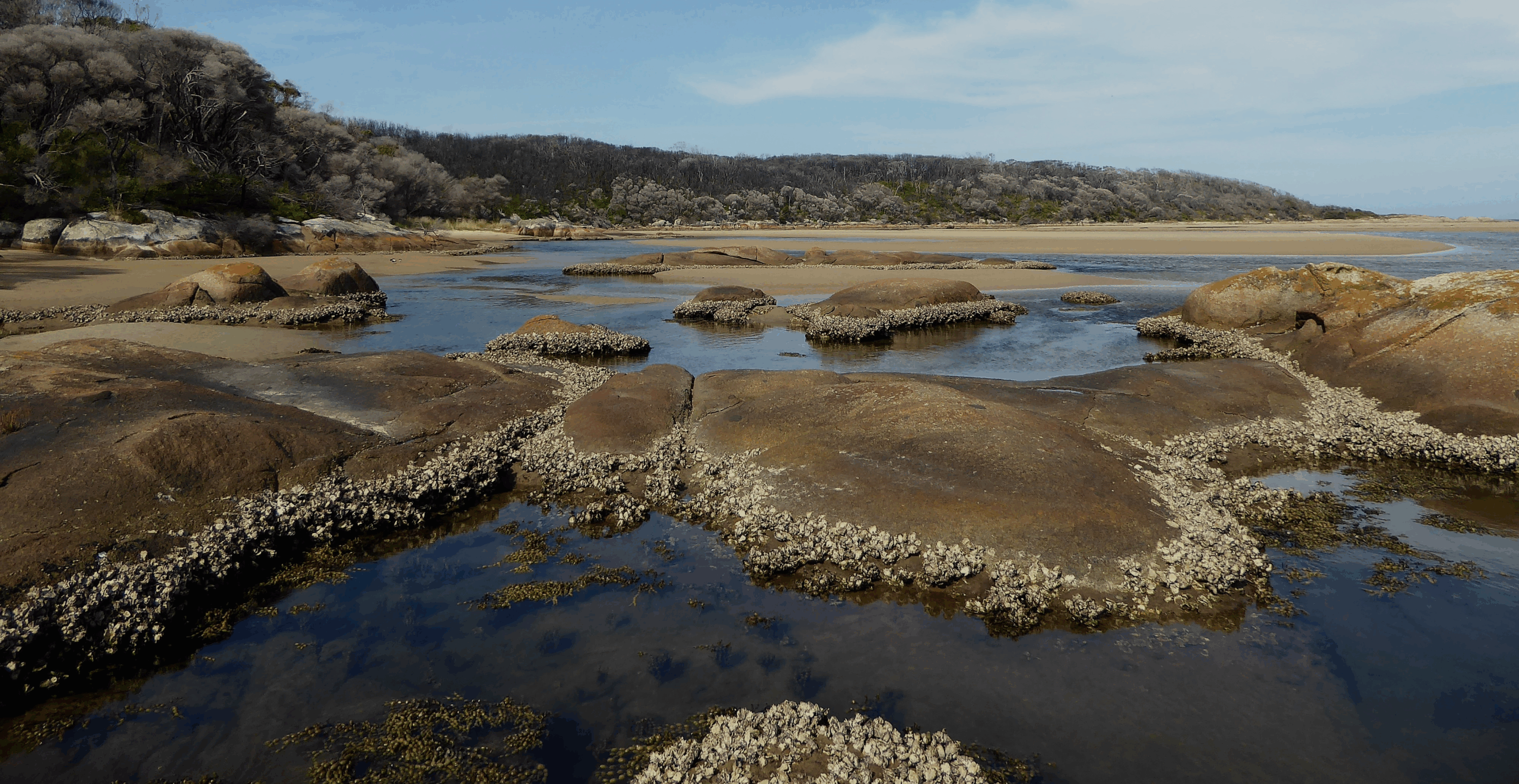

The estuary is only a short stroll from the campground. Twice each day the tides pour through the entrance, fill the channels, cover the sand flats and then recede. Many species are well adapted to this continually changing environment.

At low tide the Soldier Crabs move en masse across the sand, presenting a formidable sight to potential predators. When under threat, they spiral, out of sight, into the sand.

Club Mud Whelks, hardy molluscs, are continually on the move on the sand flats, whether the tide is in or out. As the tide flows in, the Australian Ghost Shrimps or Bass Yabbies become active, using pleopods on their abdomen to push water from the burrows to the sand surface. This action enables oxygenated water to move through the burrow.

The long, slender Shorthead Worm Eel remains buried in the sand flats during the day with only the tip of its snout protruding and hunts for invertebrates at night. The bony tip of its tail allows it to quickly burrow into the sand tail first.

Rich in diversity, the fish life in the inlet include Luderick, Dusky Flathead, Silver Trevally, Estuarine Perch, Black Bream, Australian Salmon and Tailor. In recent years fish more common in northern waters have been seen in the inlet, such as Tarwhine.

As much of the inlet is shallow, the best way to explore is by kayak or canoe. The return trip to The Rapids at the end of the tidal section is about eight kilometres. Azure Kingfishers fly from shrub to shrub along the shoreline looking for small fish. White-breasted Sea Eagles soar overhead to spot larger fish.

Heading upstream, Silvertop Ash (Eucalyptus sieberi) and Mountain Grey Gum (Eucalyptus cypellocarpa) dominate the ridge tops, while in the shelter of the gullies, Large Kanookas (Tristaniopsis laurina) draped with vines and creepers grow in the warm temperate rainforest. While the rainforest can appear to be dense and formidable, the vegetation under the canopy can be open and relatively easy to walk through.

Kayaking near the inlet’s entrance requires an awareness of the tides to avoid being caught in the strong outgoing flow. Inside the entrance, the incoming tide provides good swimming water.

From the eastern side of the entrance it is possible to follow the rocky shoreline to Easby Creek, a small estuary which is mostly closed, about a five kilometre return walk involving some rock scrambles. The return day walk further east to Red River requires careful consideration of tides and weather.

Wingan Inlet’s ocean beach extends two kilometres from the western side of the entrance to Fly Cove. Just offshore from the entrance lies the Skerries, a granite island group that provides habitat for Little Penguins and many other seabirds and the Australian Fur Seal. The seals are often seen lazing on the rocks on the eastern side of the entrance.

In the campground, on still nights, the seals can be heard bellowing and on occasions their stench can drift ashore on a southeast breeze.

The ocean beach can also be reached from the campground, a four kilometre return walk. After leaving the Bloodwood forest surrounding the campground, the walking track follows the inlet shoreline on a raised boardwalk through a dense paperbark forest containing Scented Paperbark (Melaleuca squarrosa) and Swamp Paperbark (Melaleuca ericifolia).

Closer to the beach, Southern Mahogany (Eucalyptus botryoides) provide the canopy cover and Wild Cherry (Exocarpos cupressiformis), which produce small, delicious fruit, are common in the understory. In the summer months the magnificent pink Hyacinth Orchids (Dipodium punctatum) are often seen at the foot of the Southern Mahoganys.

The ocean beach is a different and exposed environment. To the west is a short walk to Fly Cove and further two kilometres to the trig point on top of Rame Head. Here, to the north and west, lie ancient sand dunes, blown inland during ice age periods.

Looking at this natural landscape it is difficult to visualise the changes that have occurred over time, and yet it was only a matter of a few thousand years ago that the seas were much lower and vast amounts of sand were being deposited in longitudinal dunes oriented northeast-southwest.

The dunes trapped water flowing from inland, most likely creating a barrier across the Wingan River at some time. A similar natural process occurs today at Point Hicks where massive sand dunes deposit sand into the Thurra River which is then washed out to sea. Lake Elusive, accessed from the West Wingan Road not far from the campground, is a freshwater lake trapped between two sand dunes.

The Bidawal people (also known as Bidhawal and Bidwell) and their ancestors, the First Nations people of this country, have experienced these significant landscape changes during the fall and rise of sea level. On the shores of the inlet and on the rocky coastal headlands middens and cutting implements have accumulated from the thousands of years of occupation of this country by the Bidawal.

Wingan Inlet continues to be a place of great significance for its natural and cultural values and as a destination for those seeking natural beauty and solitude. The journey down the West Wingan Road provides the rare opportunity to explore an environment rich in diversity and experience and appreciate this unspoilt landscape.

Note: Wingan Inlet is remote from facilities and services, the closest being located at Cann River. The Parks Victoria website provides excellent information that assists visitors in planning their camping trip to this extraordinary part of East Gippsland (https://www.parks.vic.gov.au/places-to-see/parks/croajingolong-national-park/where-to-stay/wingan-inlet-campground).