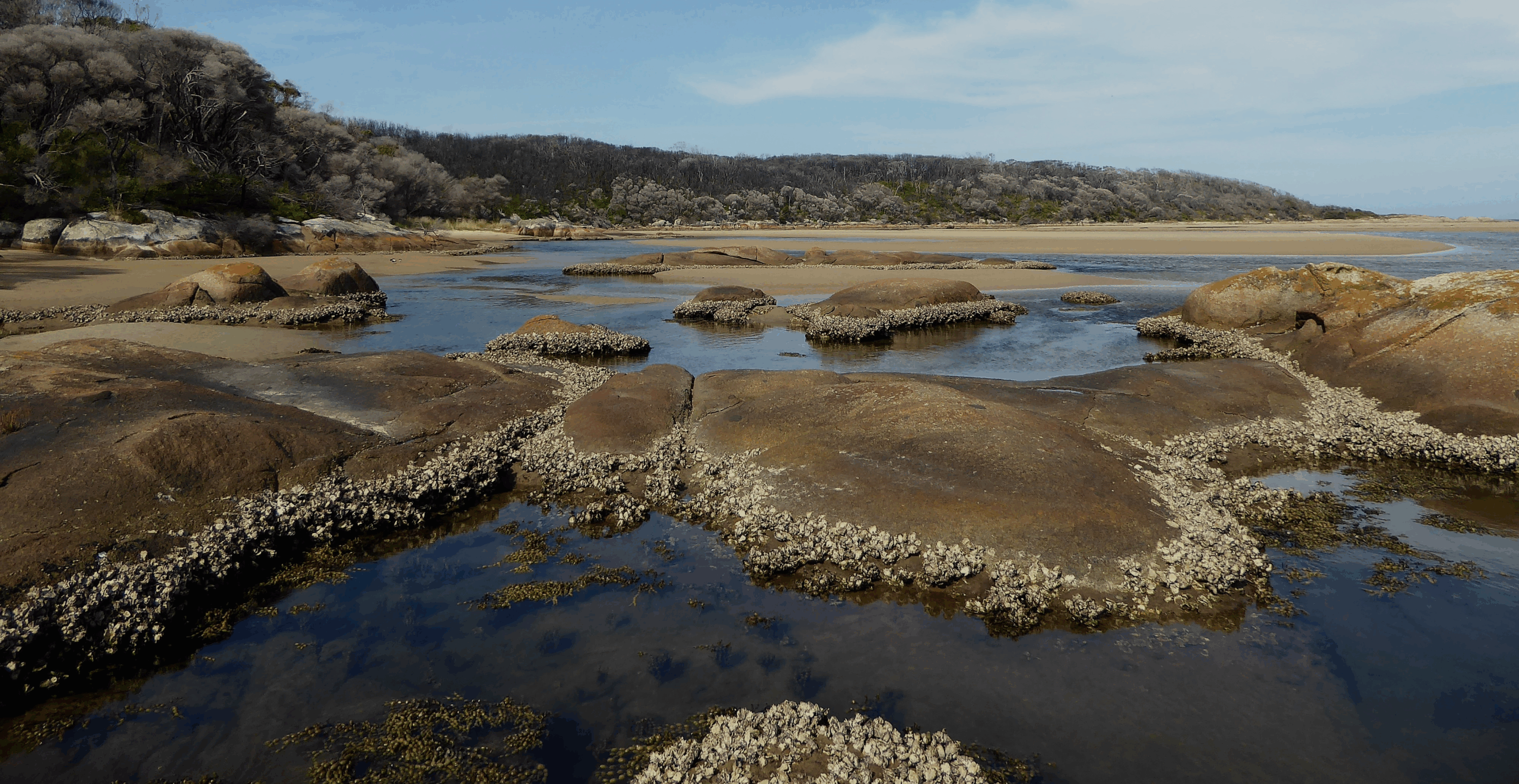

Wingan Inlet in Far East Gippsland provides ideal habitat for a famous Australian shellfish, the Sydney Rock Oyster (Saccostrea glomerata). Found in clusters around the shoreline and firmly attached to the granite rocks, this mollusc is well adapted to the twice daily inundation, extremes of hot and cold and variable currents found within the estuary’s intertidal zone.

The Sydney Rock Oyster is endemic to the Australian east coast and has a range that extends from Wingan Inlet in Victoria’s Croajingolong National Park to Hervey Bay in Queensland. It reaches maturity at three years and has a life span of 10 years.

For First Nations people, Sydney Rock Oysters provided a sustainable food source, easily carried and remaining fresh out of the water for up to three weeks in cool conditions. The shells were utilized in tool making and evidence of their widespread use and consumption can be found in the large mounds or middens located along the east coast.

First Nations people also harvested the southern mud oyster or Australian flat oyster (Ostrea angasi), endemic to southern Australian estuaries. It is larger than the Sydney Rock Oyster, but less common at Wingan Inlet.

The Sydney Rock Oyster is not only valuable as a food source. Being hardy and difficult to dislodge, the clusters of oysters protect estuary shorelines by lessening the erosion impact of waves and currents.

The structure of the oyster clusters provides valuable habitat for fish, crustaceans, other molluscs and invertebrates.

When the tide is in, oysters open up their two hinged shells to draw water across their gills and filter feed on phytoplankton or algae. These tireless creatures are major contributors to the excellent water quality of the estuary.

The abundance of oysters noted by European visitors to Wingan Inlet is testament to the thousands of years of sustainable management of the resource by the First Nations people.

In 1869 William Turton, Assistant Geodetic Surveyor camped at Wingan Inlet and wrote that his party was without meat. He reported “One good thing is we have plenty of oysters, and could load ships with them. We manage to live on them now.”

Lieutenant HJ Stanley, RN, reported following a coastal survey by MMS Pharos in 1871 that “The oysters found were very large and good, but not in sufficient quantity to create an industry, unless it were ever intended to form the inlet into a breeding place, for which it seems admirably adapted.”

News of the Wingan Inlet oysters spread and in the 1880’s, fishermen were making the dangerous journey to the inlet to take the sought after shellfish for the NSW market. In 1886 the lighthouse keeper at Gabo Island, Mr Simpson, gave assistance to a man named Glover and his three mates who reached the lighthouse after being six days without any food, apart from a few oysters. Glover said that their boat grounded on the Wingan Inlet bar and only got off after a quantity of oysters had been thrown overboard. Several days later a second attempt to cross the bar and head to sea was made and, although the boat managed to get across, it was considerably battered. Repairs having been effected, the men rowed the thirty six miles (58 kilometers) up to their waists in water and greatly relieved to reach Gabo Island.

In the late 1800’s there were reports that the supply of oysters from Wingan Inlet was considerably reduced due to the take by boat crews from New South Wales. Interest in establishing an oyster industry was growing and in 1900, Mr Mason, marine surveyor for the Commissioner of Customs, visited Wingan Inlet to assess its suitability for a lease for oyster cultivation. Mr Mason reported that the inlet was “eminently suitable for the cultivation of oysters, and that comparatively little expenditure would be needed to secure good returns.”

In the early 1900’s there is little information that describes any oyster cultivation activity at Wingan Inlet, other than in a 1901 report of the wreck of the Steamer Federal a mention of a man named Anderson camped at Wingan Inlet and in charge of the oyster beds.

“The Wingan River, A Gem of the Victorian Coast” by EJ (Edwin James) Brady in 1911 provides a detailed and entertaining account of a camping trip to Wingan Inlet and the consumption of local oysters. Brady, with his mate, Charlie Cameron from Double Creek, rode the coastal route from Mallacoota and camped, fished, hunted and swam over three days. While his mate was looking for a lost horse, Brady devoted himself to photography and eating, writing “Wingan oysters are justly regarded …. as second to none”.

The quality of the Wingan Inlet oysters was also noted by Lieutenant-Colonel JM Semmens, Inspector of Fisheries and Game during his inspection of the oyster beds in 1919. He was “very much impressed with the possibilities of the extension of the Wingan rock oyster beds by proper culture”. He went on to describe the oysters as “the finest in Australia and most of them are in beautiful condition”. Lieutenant Colonel Semmens’ journey to the inlet was not easy, requiring a pack horse with a guide and a day in the saddle.

Recommendations to the Fisheries and Game Department following Lieutenant Colonel Semmens’ visit reinforce the enthusiasm for developing the oyster fishery within Victoria after the First World War. And there was great praise for the Wingan Inlet oysters. “Indeed, it is doubtful whether more palatable rock oysters exist in any part of the world” commented the Melbourne Herald at the time.

The arrangements for transporting the Wingan Inlet oysters were arduous, involving a boat trip to Cunninghame (now Lakes Entrance), a steamer trip to Bairnsdale and the journey completed by train to the Melbourne Market.

Interstate rivalry was a factor in the plans to develop Victoria’s oyster fishery after the First World War. When the Minister for Fisheries, Dr Stanley Argyle, visited Wingan Inlet in 1924, he did not see why Victoria should not emulate New South Wales in the cultivation of the oyster. Dr Argyle said that if he had his way, the New South Wales growers who had the run of the Melbourne market would have to meet competition from a little closer to home.

In 1928, in spite of the great acclaim the Wingan Inlet oysters received, it was becoming clear that there were challenges in their cultivation. An investigation by TC Roughley, economic zoologist of the Technological Museum, Sydney found that it was hard to remove the oysters from the hard granite rock without substantially damage. He recommended the use of mangrove sticks that could be easily transported to the inlet and laid out to grow the oysters. This technique was used elsewhere in NSW and described by TC Roughley’s in 1925 in “The Story of the Oyster”.

Following a tender process in 1929, the Fisheries and Game Department received four applications for licences for intensive oyster cultivation at Wingan Inlet. This came at a time when the oysters were depleted and it was recognised that it would take some years before marketable quantity would be available for the Melbourne market.

The Chief Inspector of Fisheries and Games, Mr Lewis, together with the Chief Secretary, Mr McFarlane made an inspection of the oyster culture areas in 1934 and said that it would be possible for all of Melbourne to be supplied with oysters from Wingan Inlet. Ten leases had passed the experimental stage and were flourishing.

The recovery of the inlet’s oysters was short lived due to heavy rains in 1937 reducing salt water levels, causing undernourishment and mortality. A proclamation prohibiting the taking of oysters was introduced, and the sole lessees, Warn and Boller halted taking out the recovering oysters.

In 1952 the Weekly Times lamented that Wingan Inlet oysters, the “world’s finest”, farmed by New South Wales fishermen operating from just across the border, no longer found their way to the Melbourne Market.

Regardless of the efforts of and optimism shown by government officials, experts and politicians over the years, a sustainable oyster fishery was not achieved at Wingan Inlet. There was much discussion about practices for improving cultivation, such as the establishment additional oyster beds, but there is little evidence of this today.

At some time a long row of oyster rocks were placed across the flats about 1.5 km from the inlet’s entrance. It is unclear whether these were positioned by the New South Wales oyster fishermen or earlier by First Nations people and their purpose and history requires further investigation.

Over the last few decades the population of oysters around Wingan Inlet’s shoreline has re-established and continues to contribute to the health of this magnificent estuary. As the world’s climate changes, monitoring of this oyster population could provide a greater understanding of the impacts of rising temperatures and water acidity. With the increasing pressures on our natural systems, the need to protect this remarkable place takes on even greater importance.

Acknowledgement: The information supporting this article was sourced from newspaper reports on https://trove.nla.gov.au/ and the recollections of many who have experienced and enjoyed Wingan Inlet over the years.

Leave a Reply